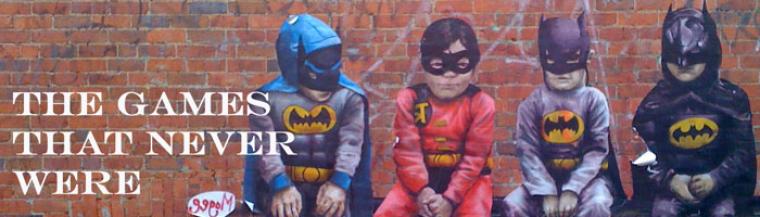

Sequels, re-boots, stagnation - it's a pity that games rarely attempt the revolutionary, the never-before-seen, or even the impossible. The Games That Never Were is a series of thought-experiments: Games that never existed, and that may very well never come to be. This time, Mike Grace from Haywire Magazine premieres as the first contributor in English - and takes us to a familiar place that's feeling brand new. I'd play that.

Gotham, the city, is almost as famous as it's playboy billionaire/chiropteran-influenced-superhero. Up until now, only vague fragments of the city have been released. With the latest release, you can finally go into the infamous city itself, see how it ticks, and influence its development.